Wandle Restoration Part XIV

May 5, 2007

Trout tank trilogy: part 3

24 February

Remember that trout habitat chart from the Wild Trout Trust’s “Survival Guide” in my article last September – with recommendations for the structures, depths and speeds of water preferred by trout at different stages of their lives?

With swim-up imminent, I’m keen to make as much of my local habitat as I can. So I take a few hours off work this afternoon, with the best possible excuse for messing about in the river…

Over past seasons, I’ve already done quite a lot of subtle morphological tweaking in the old wheel pool of the mill, moving chunks of concrete and masonry out of muddy deeps to make pinch points in the current, converting a slow, featureless flat into a much more interesting 30 yards of water.

Today, I’m concentrating on one of the shallower glides just downstream, where the winter rains accumulated in the Wandle’s aquifer now swirl smoothly out from the old bridge arch. Here, I’ve already deepened one section by digging out a concrete kerbstone, and dragging it upstream to form a useful feature. Now I walk upstream again, select a few strands of ranunculus from beds that survived the catastrophic low flows two summers ago, wrap them round small lumps of building waste, and heel them into position on either edge of the glide. It’s not quite the recommended river-mender’s method of lashing weed round “snowshoes” of willow, but I don’t have enough to do that properly. And after all, this is basically how ranunculus propagates naturally…. I’m just lending it an extra helping brick.

Between the new beds of weed, I stud the gravels with more half-football-sized lumps of concrete. Swim-up trout fry are highly independent: in the wild, at least, they can’t stand the sight of each other, and territories are based as much on competitive visibility as actual square footage. So although the books give a figure of just a single fry per square metre, I’m hoping to maximise habitat in this stretch simply by cutting off a few sightlines.

When I’ve finished, I lug the usual collection of bottles and beer-cans up the bank, and look down on my handiwork from the bridge above. It’s satisfying to see what a difference you can make by tweaking some substrate: if any of the fry in my tank do survive, and the upper Wandle doesn’t boil dry, this stretch should provide long-term habitat for at least a few of them.

Back at the tank in my dining room, I lift the lid to float another pinch of fish-food across the surface. Not a flick of a fin: their yolk-sacs are almost completely absorbed, but the fry still stay glued to the gravels. Ah well, time’s probably on our side.

25 February

Swim-up!

At first, when I try the feeding experiment again today, nothing happens. But just as I’m closing the insulating curtains round the tank, there’s a sudden flash of movement – and a single little fry shoots up from the bottom to bash its head on the mirrored ceiling of the surface, grabbing a microscopic grain of fish-food.

Soon, two or three more are joining in: you could almost call this a competitive rise. We’re in business!

1 March

Scattering pinches of food into the tank, I wonder what it’s really made of. The fishy smell hints strongly at processed sand-eel or sprats – ecologically-dubious and a long way from the chopped egg, powdered liver or “fine scraped meat” that used to be fed to fry in the days of Alfred Smee or even Henry Williamson. Then again, this bonanza won’t last long, and my little fish will soon be out in the river, fending for themselves with the advantage of a few weeks’ artificial “sea-feeding”.

Speaking to a fisheries friend the other day, I had another of those moments of forehead-slapping-how-could-I-not-have-thought-of-that insight: of course, it’s important not to release little trout too early in the year, or there won’t be sufficient numbers of ephemerid nymphs and other macro-invertebrates to sustain them. Here on the upper Wandle I’m pretty sure these fry won’t have that problem – blanket hatches of olives aren’t exactly common, and midges are a far more likely diet. But it’s always sensible to remind yourself of the bigger ecological picture, how every link in the chain of life has evolved inseparably from every other, and how the great seasonal cycles affects even my own small hatchery.

At the other end of the size scale, how could a trout that hatched too late cope with swallowing a grown-on shrimp or hoglouse half its own size? It’s a funny but sobering thought.

3 March

All over southern Britain there’s a total lunar eclipse tonight, with clear skies that actually let us see it. We step out onto the front doorstep several times to watch it develop, creeping towards totality at about 10.45pm, finally glowing dull orange-red with darkness at its heart, and the sort of textbook globularity you hardly notice in the flat bright moon of every normal night.

I’ve been staring at the new-style moon for several minutes before I suddenly see what it really looks like: a giant trout egg in the sky. My wife tells me I’ve got fish on the mind: she’s right…

8 March

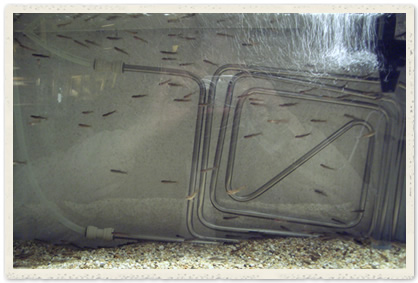

As the days pass, more and more 1-inch fry are coming up on the fin.

Increasingly active, some are holding high in the bubbling oxygen around the aerator pump: others surf the micro-currents like kites, clearly revelling (OK, let’s be anthropomorphic about this) in total 3-dimensional mobility. They’re changing colour, too: less dark, more translucent tan, re-camouflaging to match their new mid-water environment.

Adipose fins and all – already, you couldn’t mistake them for any other kind of fish. Crouched in front of the tank, I feel as if I’m diving in a crystal backwater of the Soca, watching trout hovering delicately through water that’s clear as air over a clean gravel bed. Transcendental stuff… truly a whole new scaled-down angle on familiar trout.

15 March

It seems to be working, this experiment Gideon and I agreed on last month. Holding the temperature down, keeping the tank dark, we’re inhibiting algal and bacterial growth both on the gravel and in the water.

To all appearances, it’s keeping the trout healthy too. By way of comparison, one of the schools in our “Trout in the Classroom” programme suffered a power cut last weekend – the beer chiller stopped, the temperature in the tank soared to 16 degrees, and now they’re battling algae and losing several fish a day.

Still, I’m secretly starting to wonder about the dark shoal of fry that’s hugging the shadows in the corner by the aerator tube. Most of their midwater comrades seem to forget their nerves about 90 seconds after I’ve opened the lid to feed them, darting up happily to intercept the feast, developing the beginnings of a hierarchy of size and colour – but the bottom-dwellers stay strangely inactive.

Are they getting their fair share of the food that’s circulating through the water column?

Are they even trying to get it?

23 March

Are those dark fish feeding? The answer, it seems, is no.

This morning, more than a dozen little corpses lie in a cluster on the gravel – dark, thin, skeletal in contrast to the bumptious bully-boys of the upper layers. Bring out your dead. I collect them with the turkey baster and a heavy heart.

26 March

The Great Dying continues for days with a terrible inevitability. Trying to do what I can, I increase the pinches of food I’m scattering into the tank, but to no avail. Morning and night, now, I’m scooping up dead, dying, undernourished fry.

Could this be the payback for all those other advantages of keeping the temperature down – for not encouraging these cold-blooded little creatures into greater activity with an extra couple of degrees on the thermometer?

Yet I still think it’s unlikely that a natural river’s temperature could be relied upon to rise so dramatically, at just the right time to stop starvation in the fry that don’t work out how to swim up and feed by themselves.

So is this actually another population pinch-point – a bottleneck on fishery productivity, but one that’s not widely discussed in the literature of conservation? Independent of habitat structures, competition or predation, but governed by thermal fitness and ability to function through a range of external temperatures – it meshes with my own understanding of how natural selection might work. More research needed?

28 March

With about 70 fat, active, light-coloured survivors from my original 200 or so hatchlings, mortality is finally levelling off – and not a moment too soon. After all, today’s the second phase of our schools’ trout releases, and my own are Section-30-booked for freedom tomorrow.

By now I’m taking risks, feeding them as much as they can eat, gambling that the biofilter won’t quite overload before they’ve packed in the protein. The water’s finally looking cloudy – but maybe that’s only because I couldn’t get the gravel siphon to work properly, merely succeeding in mobilising fluffy, gravelly mould into the moving water column. More ominously, extracting about a fifth of the tank’s volume and replacing it with tap water that’s stood overnight to release its cargo of chlorine actually seems to make the problem worse.

Note to self: must work this out before next year, when I want to try the outdoor chiller-free version of this set-up, relying on a late spring and the cold north wall of the house to keep the temperature down. Well, it worked in Sheffield…

Finale

Afternoon in Morden Hall Park, watching no fewer than 7 schools enthusiastically releasing their trout into manicured National Trust surroundings. It’s great to see the faces of the kids, watching intently as their fry float away to freedom, cheering and clapping them off into their new home. Now, it’s my turn.

Turning off the beer-chiller, silence descends as a shock. I leave the oxygen pump running for as long as possible whilst I’m reducing the water level in the tank, then sweep the aquarium net back and forth to capture my little trout. By the time I’ve caught most of them, the rest are properly spooked: in fact, one escapes notice altogether and only emerges from the gravel, still alive and well, when I’m washing it for Gideon afterwards.

And so out to the river, carefully distributing my small fry into pockets of slack-water habitat to help them acclimatise quickly, watching them hovering away to mingle with the sticklebacks in the Wandle’s headwaters. It’s surprising how quickly they disappear.

Will I see them again in the future, rising to flies, maybe even hitting one of mine?

Time alone will tell… but they’re off to a good home.

← Read previous instalment | First instalment ↑ | Read next instalment →